Vincent de Paul and Mohandas Gandhi:

Five Commitments That Sustain Leadership

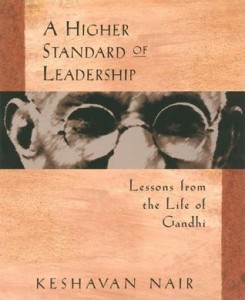

This essay explores aspects of the leadership of Vincent de Paul and Mohandas Gandhi through a leadership framework developed by Keshavan Nair, author of A Higher Standard of Leadership: Lessons from the Life of Gandhi. Born in India, Nair was 15 years old when Gandhi was assassinated. Nair later began a lifelong study of Gandhi’s leadership practices. He moved to the United States in 1959. Prior to his death in 2002, he served as a consultant to corporations and government agencies, and taught at Ohio State University and the Indian Institute of Technology in Kampur, India.

This essay explores aspects of the leadership of Vincent de Paul and Mohandas Gandhi through a leadership framework developed by Keshavan Nair, author of A Higher Standard of Leadership: Lessons from the Life of Gandhi. Born in India, Nair was 15 years old when Gandhi was assassinated. Nair later began a lifelong study of Gandhi’s leadership practices. He moved to the United States in 1959. Prior to his death in 2002, he served as a consultant to corporations and government agencies, and taught at Ohio State University and the Indian Institute of Technology in Kampur, India.

Though they lived centuries apart, Vincent de Paul and Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi are viewed as examples of transformational leadership. Both men became in their lifetimes beloved by the people of their country and throughout the world. They continue to inspire leaders today. They achieved this greatness through profound dedication to a lifetime of public service, through which they themselves were transformed as well.

The achievements and notoriety of Vincent and Mohandas may in part be due to their many other similarities. To begin with, both men studied law, and as young men both anticipated lucrative professional careers (although Vincent’s chosen route to improving his peasant background was the Catholic priesthood, a quite typical choice in his day). As young adults, however, both Vincent and Mohandas experienced a conversion to the plight of the poor, forsaking any personal gain from what became their lifelong works.

For Vincent, his conversion came as he confronted the needs, both spiritual and physical, of the sick and poor living in his early parishes. For Mohandas, it came through his own experiences as the object of racial discrimination while working in South Africa. For the remainder of their lives, both men dedicated themselves to service and advocacy on behalf of the poorest and most despised people in their respective societies. Interestingly, both also advocated for the involvement of women in public life.

Vincent and Mohandas also both were deeply religious, and sustained their dedication to service and societal transformation through a commitment to their beliefs, principles and values.

Lastly, both men spoke freely of their faults, exposing their own struggles to live up to their personal ideals. Gandhi’s biography (My Experiments with Truth) is remarkably humble and honest. Vincent tells us that he asked God to change his “irritable and forbidding disposition” (Maloney.167)

Five Commitments That Sustain Values-Centered Leadership

Nair’s leadership framework, which emerged from his study of Gandhi’s life and leadership, consists of Five Commitments:

1. Commit to Absolute Values

2. Commit to the Journey

3. Commit to Training Your Conscience

4. Commit to Reducing Attachments

5. Commit to Minimizing Secrecy

Nair’s views the five commitments as interwoven, creating “a process for striving toward a single standard.” In other words, for Nair, the five commitments form the foundation upon which his single, “higher standard,” of leadership rests. Nair argues that leaders ought to live by that higher standard in both their private and public lives. Nair writes:

We have been led to believe that there is one standard for private morality and conduct and another for public morality and conduct. We have come to accept that a lower moral standard is necessary to get things done in the real world of politics and business (13).

To return to living by a single standard in both our public and private lives requires more than talk; it requires practical guidelines for the daily journey. Explains Nair:

It is not enough to exhort people to live by a single standard; we have to make it practical. We need guidelines that individuals in all segments of our society – from potential leaders in our high schools and universities to parents and teachers, from leaders in our communities to national and international leaders – can understand and try to follow (16)

We can learn something about how to enter this process of committing to a higher standard for ourselves from the lives of Vincent de Paul and Mohandas Gandhi. We begin with Nair’s description of the five commitments in the life of Mohandas Gandhi, and conclude with a look at Vincent’s life and how he practiced these commitments in his own life.

We can learn something about how to enter this process of committing to a higher standard for ourselves from the lives of Vincent de Paul and Mohandas Gandhi. We begin with Nair’s description of the five commitments in the life of Mohandas Gandhi, and conclude with a look at Vincent’s life and how he practiced these commitments in his own life.

1. Commitment to Absolute Values

For Mohandas Gandhi, religion was the ground from which his sense of values sprouted. Although Hinduism was his religion by birth and later by choice as an adult, Gandhi explored and spoke positively of many religions. He embraced the “golden rule” of all religions: to treat other human beings as ourselves (19). He expressed this in his commitment to nonviolence and in speaking out on behalf of the “untouchables” of his society.

Another absolute value for Gandhi was Truth. Initially, he spoke of God as truth, but later in life came to reverse that idea as he became committed to the notion that “Truth is God.” Gandhi defined truth broadly: “There should be Truth in thought, Truth in speech and Truth in action” (20).

For Nair, identifying absolute values is not enough. They must be operationalized. “Gandhi operationalized the absolute values of truth and nonviolence when he established his ashram.” In the ashram, Gandhi lived his values, requiring that every resident, even himself, participate in all forms of manual labor including cleaning the latrines, a role traditionally reserved for untouchables (25).

2. Commit to the Journey

Gandhi’s choice to establish his first ashram in South Africa and begin to live his values was only a beginning. As Nair writes: “It is easy to believe in something intellectually, but living your beliefs takes a commitment – and that is what staying on the path requires….To move along the path, we must evaluate all of our actions in terms of [our] absolute values…and increase the number of actions that adhere to them” (27-28).

Gandhi’s secretary, Pyarelal, describes how Gandhi, at age seventy-seven, still adhered to his values one day at a time:

Daily he held a silent court within himself and called himself to account for the littlest of his little acts. Nothing escaped his scrutiny (29).

Nair also notes that Gandhi did not act alone. Neither did Vincent. Both formed a community of support around themselves to help sustain them in their commitment. “It is important to that we, too,” writes Nair, “associate with colleagues who share our commitment to be on the path” (30).

3. Commit to Training Your Conscience

The notion of “training your conscience” is not one that receives a lot of attention in our culture of expedience, especially given Western culture’s additional focus on “What’s in it for me?” Nair, however, suggests that maintaining the path of commitment to a single standard of conduct “requires that we evaluate our actions in a moral framework.” A trained conscience, writes Nair, offers “disciplined, moral reasoning that tells us what we ought to do.” We begin this training by applying the absolute value of truth to our everyday statements and actions (33).

This training requires time, and a commitment to “the discipline of regular personal reflection.” Nair writes:

I have found that the simplest – but in many ways the most profound – question I can ask myself is, “Did I treat others as I would like to be treated?” (34).

In response to criticism that such time for personal reflection is hard to carve out of our busy work lives, Nair has a solution: get it on your calendar.

I do not believe that disciplined reflection takes time away from work; it sustains the spirit and increases the intensity and quality of work….If you consider personal reflection as a meeting with yourself, it can be scheduled just as your meetings with others are (35).

Mohandas trained his conscience in part by reading and memorizing the Bhagavad Gita, a sacred Hindu text. “It became his ‘infallible guide of conduct,’ his ‘dictionary of daily reference,’ and ‘the book par excellence of the knowledge of Truth’” (Nazareth, 17)

To begin to understand and strengthen our own conscience, we might ask ourselves:

4. Commit to Reducing Attachments

We all have attachments that develop from the contexts of our lives. “Attachments are relationships, possessions, privileges, and other components of our life we do not want to give up,” writes Nair. These attachments may be desirable ones, like our attachments to family, but some can be detrimental to us and to others, such as an attachment to power, privilege, and ever more possessions. Both Vincent and Mohandas were aware of this, and spoke about it.

As he entered into public life, Mohandas Gandhi asked himself what he must do “to remain absolutely untouched by immorality, by untruth, by what is known as political gain.” His first practical step in response to his desire to remain morally strong was to choose voluntary poverty. He simplified his life and lowered his standard of living.

Following the example of Gandhi in our time, suggests Nair, might mean taking time to reflect on the rationale for the various attachments we have acquired. For a leader, some attachments “are necessary for efficiency, some represent the symbolic role of leadership, and others are part of the compensation of the position.” However, “every privilege should assist in meeting organizational objectives – and it is the objective you should be committed to, not the privilege” (Nair. 40-41.)

Another way, perhaps, to simplify our lives is related to Nair’s final commitment, which involves always being open and truthful in our interactions with others.

5. Commit to Minimizing Secrecy

A truthful examination of our attachments is aided by a commitment to minimize secrecy. “A commitment to minimize secrecy forces us to think of the consequences of our actions and provides a discipline that helps us stay on the path” (43).

Nair speaks to the benefits of minimizing secrecy in business and organizational life. “Leaders who share the strategy, financial performance, and success of the corporation with their employees create a sense of partnership with them. Partners are willing to put in the effort to develop new ideas, work long hours in emergencies, and to act for the common interest over self-interest, thereby building competitive advantage” (45).

Nair stresses the relationship between sharing information and developing a culture of trust within organizations. He writes: :

Secrecy is the enemy of trust and is responsible for much of the distrust that exists between business and society, corporations and customers, management and employees….How can leaders ask for the trust of the people they lead if they are not prepared to share information? (46).

Mohandas Gandhi was of the opinion that individuals and organizations committed to truth and nonviolence could have no secrets. He wrote: “Secrecy, in my opinion, is a sin and a symptom of violence, therefore, to be definitely avoided.” Gandhi lived a life committed to openness. His autobiography, The Story of My Experiments with Truth, exhibits extraordinary honesty and candor, concealing none of his weaknesses or mistakes (43).

The Five Commitments in Vincent’s Life

1. Commit to Absolute Values

Vincent urged his companions in service to adhere to five virtues, speaking often about their importance to sustaining a life of dedicated service. These five virtues, offered by Vincent in the language and concepts of his day, summarize his values. They are: simplicity, humility, meekness, mortification and zeal.

Vincent often stated that the foundation of his beliefs and actions was modeling Jesus, who came “to bring good news to the poor…, to proclaim release to the captives and recovery of sight to the blind, to let the oppressed go free” (Luke 4:18). His focus on this passage allowed him to value the poor as dignified human beings beloved of God.

Vincent, like Gandhi, clung to truth as an absolute value. He expressed this in his description of the virtue of simplicity. “It also means doing things without any double-dealing or manipulation, our intention being focused solely on God” (Maloney. 163).

2. Commit to the Journey

Like Gandhi, Vincent’s response to the needs of the developed into a life-long journey. Vincent saw himself following in the footsteps of Jesus, the Evangelizer of the Poor. He saw his work as continuing the work of Christ.

Vincent was still committed to the task of serving the poor even as old age and illness slowed him down physically. As an old man, he once said, “As for myself, my age notwithstanding, I do not consider that I am excused from the obligation of laboring in the service of the poor” (ibid. 170).

3. Commit to Training Your Conscience

Vincent was a man of action. He said, “Let us love God, but let it be with the strength of our arms and the sweat of our brows” (ibid.31). At the same time, he knew of the value and encouraged setting aside time to connect with our inner life. “You must have an inner life; everything must tend in that direction. If you lack this, you lack everything.”

Both Vincent and Mohandas eventually set aside one day a week for quiet and reflection.

4. Commit to Reducing Attachments

Vincent’s approach to detachment is revealed in how he spoke of the virtue of simplicity as seeking “an unadorned lifestyle.” He urged his companions in service to avoid acquiring “vain and useless things,” and to use “with great simplicity the things that have been given to us” (ibid. 39). Vincent saw this detachment as liberating, allowing himself and others “to go anywhere, to do anything, to brave all hardships” (ibid. 76).

5. Commit to Minimizing Secrecy

Vincent de Paul spoke often of the need for openness and honesty in all interactions. He once wrote, “…they that use craftiness and duplicity are in constant fear lest their cunning be detected, and lest in consequence other people cease to have confidence in them (ibid. 163).

![]() Kesavan Nair was inspired in his life and work by the example and teachings of Mohandas Gandhi. As Vincentians we seek to draw the same inspiration from the examples and teachings of Vincent de Paul. Nair’s five-commitment leadership framework, and the teachings and actions of Vincent de Paul and Mohandas Gandhi explored through this framework, combine to form a practical guide for our own values-based leadership and service.

Kesavan Nair was inspired in his life and work by the example and teachings of Mohandas Gandhi. As Vincentians we seek to draw the same inspiration from the examples and teachings of Vincent de Paul. Nair’s five-commitment leadership framework, and the teachings and actions of Vincent de Paul and Mohandas Gandhi explored through this framework, combine to form a practical guide for our own values-based leadership and service.

We look forward to hearing comments on how helpful you find this framework for your own leadership development.

.

Reflection Questions

What absolute values do I believe are essential in my personal and professional life?

How today have I acted in ways consistent with my absolute values? This week? Over the years?

If Truth is an absolute value for me, what does that mean in practical terms with respect to members of my family, my employees or colleagues, my clients or constituents?

Who are the people who share my values and commitment, and help keep me on the path?

What are the privileges associated with my current leadership position?

What is my relationship with those privileges?

How do I feel about “the stuff” in my life? Would it help to have less?

How consistent am I in communicating essential information to members of my team?

How honest am I with myself and with my colleagues about my own strengths and weaknesses?

How do I invite others to share their desires, hopes, and concerns with me?

Maloney, Robert P., The Way of Vincent de Paul: A Contemporary Spirituality in the Service of the Poor. New York, NY: New City Press.

Murphy, J. Patrick, C.M.“Servant Leadership in the Manner of St.Vincent de Paul,” in Vincentian Heritage, Vol. 19, Number 1, 1998 and Burns, J.M. (1978) Leadership. New York. Harper & Row. Used with permission.

Nair, Keshavan. A Higher Standard of Leadership: Lessons from the Life of Gandhi (San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler. 1994. Used with permission.

Nazareth, Pascal Alan, Gandhi’s Outstanding Leadership. Bangalore, India.: Sarvodaya International Trust. 2007. 17

http://gandhifoundation.org/aims/

Edited by Patricia M. Bombard, BVM, D.Min., Director, Vincent on Leadership: The Hay Project, DePaul University, Chicago, IL USA